Dust in the workplace is either a nuisance or a valuable product, it can sometimes be both. Either way, it needs to be controlled.

If dust is a nuisance, you will need to control it for the health of your workers or for the quality of your product.

If dust is a valuable product, you will need to contain it inside your processing equipment to prevent product loss.

But, if workers come into contact with hazardous materials or potentially combustible dust, you must prioritise worker safety.

This article explains how to choose a suitable mechanism to control different types of dust and the explosion hazards of a local exhaust ventilation (LEV) system.

These are also referred to as ‘engineering controls’.

Combustible dust hazards in the working environment

All dust in the workplace must be controlled. However, not all dust needs to be extracted at source by a local exhaust ventilation (LEV) system.

Instead, next steps depend on the toxicity, the expected amount of dust released and whether the dust is flammable.

Toxicity vs flammability

From a toxicity point of view, COSHH (Control of Substances Hazardous to Health) regulations are relevant.

As a rule of thumb, dust concentrations become a COSHH hazard in the order of milligrams per cubic meter (you are likely exceeding limits if you can see a footprint in the dust at the end of a shift) and an explosion hazard by the order of grams per cubic meter (you can’t see through the dust cloud).

COSHH

Each type of dust will fall into a COSHH Hazard Band [1] from A-E (Band A is the least hazardous and Band E is the most hazardous).

Although some vapour substances are non-hazardous, all dusts are hazardous and need to be controlled.

Less stringent control measures, such as general ventilation, may be enough for non-toxic dust releases in small amounts.

However, an LEV system may be required for more toxic dust or other hazardous properties if there is the potential for larger than expected dust releases.

This often includes bag slashing and emptying or when knocking out a sand mould.

Hazard band E includes carcinogens and dust which causes occupational asthma (such as wood dust and flour).

You can check what control measures are required by using the COSHH guidance documents for your industry available from the HSE website and the COSHH e-tools.

DSEAR and combustible dust

Many dusts are flammable. This includes most metal dust (aluminium is especially explosive).

Furthermore, combustible dust can include any dust that is organic in nature (wood, sugar, tea etc).

It must also be noted that fine dust is more flammable than coarse dust as more surface area is exposed to oxygen (particle size).

For example, icing sugar is more flammable than granular sugar.

Normal operations

In normal circumstances, operators will not be exposed to explosive dust clouds as this will exceed COSHH control levels, but there are, however, two exceptions.

Exception one

While COSHH is applicable to background dust concentration and expected surges of dust associated with specific tasks, DSEAR is applicable to ‘foreseeable abnormal operations’.

This would include scenarios such as fan failure causing extraction to stop, a torn ‘big bag’ (also referred to as a flexible intermediate bulk container (FIBC)) or an inflatable seal suddenly failing causing the contents of a mill to be released into the work area.

Under these scenarios, dust may be released unexpectedly in flammable concentrations.

A secondary dust explosion

A ‘Secondary Dust Explosion’ describes a scenario where there is an accidental, yet relatively small primary explosion that, on its own, may have caused limited injury or plant damage.

However, if there are layers of deposited fine dust in the area, these materials can become dislodged by the primary explosion causing a widespread flammable dust cloud.

If ignited by the primary explosion, fires, catastrophic material damage and loss of life can result.

Normal operations: exception two

The second exception is when an LEV is used to control dust for COSHH purposes.

The unintended consequence of combustion is that the finest fractions are removed and collected in explosive concentrations at the dust collector.

For most manufacturing situations, explosive dust clouds are only found contained inside the equipment.

Some examples are a hammer mill or various types of dryers.

However, LEV systems are often required to protect operator health.

These systems provide a localised ‘vacuum’ to remove dust from the operator’s location.

Given that the finest fraction is most likely to be airborne, the extracted air contains mostly fine dust.

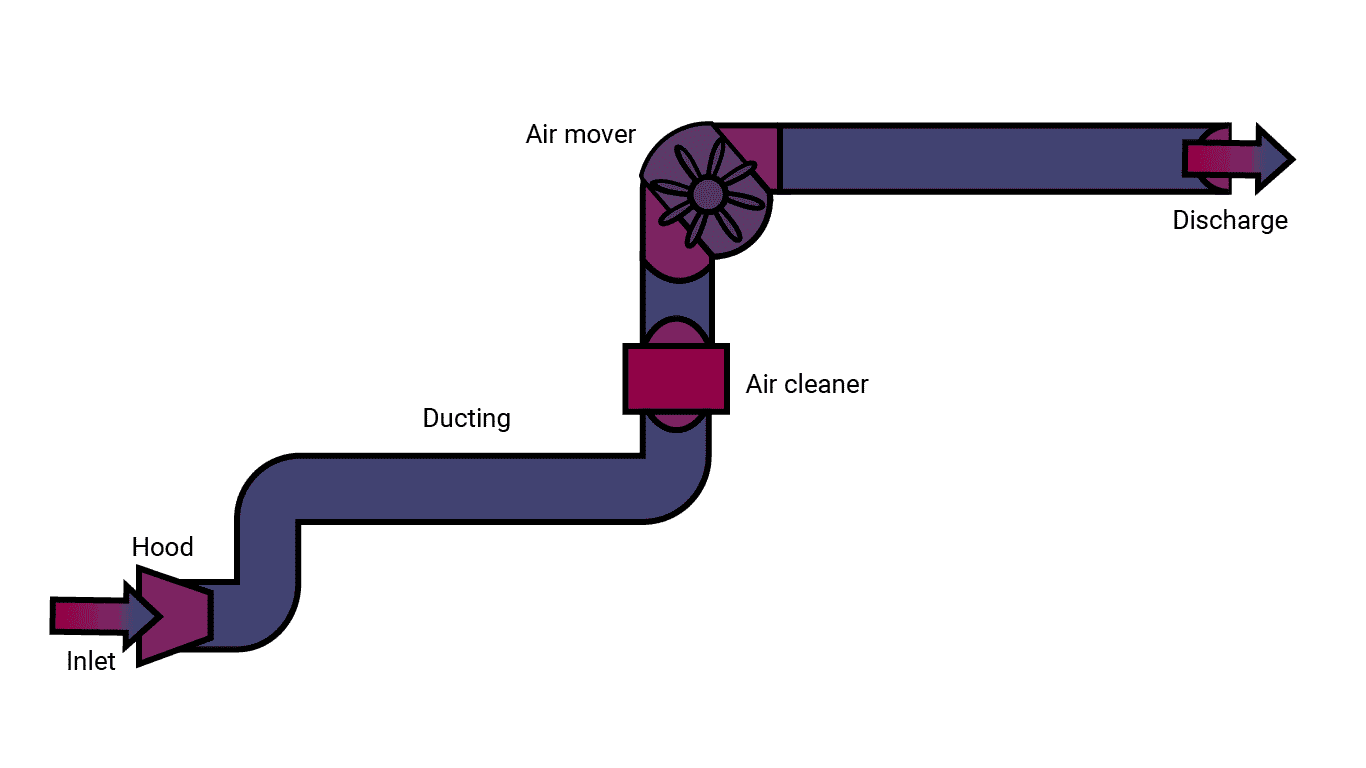

LEV systems and vacuums

To protect the environment and the extraction machinery, the dust removed with the vacuum is usually filtered before the clean air is discharged or recirculated.

This fine dust forms a ‘filter cake’ on the ‘dirty’ side of the filter and thus the filter will need to be cleared periodically.

If the dust load is light, there can be a simple shake-down mechanism.

If the load is heavier, compressed air is blown in pulses in the opposite direction of dust flow to force the filter cake to fall off into a bin.

Either of these clearing mechanisms will create a cloud of fine dust between the dirty side of the filter and the dust collection bin.

Example LEV System

If the dust is flammable, this dust cloud may be explosive, and ignition must be carefully avoided.

It is important that the LEV system is used and that they operate properly.

At times, the extraction system is not used, either because it is using too much power or because too much valuable product is being lost.

Evading a dust layer

Apart from the obvious COSHH risk, the above example may lead to dust accumulating on surfaces and the risk of a secondary dust explosion.

LEV specialists can advise on the positioning of dampers and optimising power consumption for the system.

It is a statutory requirement that the installation of an LEV system [2] must be inspected and tested at least every 14 months, although sometimes less.

This, and further combustible dust testing, must be carried out by properly trained engineers, usually outside LEV contractors.

Avoiding dust explosions – mitigation equipment

Dust collectors that handle explosive dust must be fitted with explosion mitigation equipment.

If there is an explosion in the dust collector, the flame front should not travel back into the upstream equipment or the general workplace.

Backflap valve

This is done by including a backflap valve in the ductwork before the dust collector.

This isolates the dust collector in the event of an explosion as the flap will be forced closed by the backwards pressure.

Since most dust collectors are not designed to hold pressure, an explosion will likely cause an unpredictable and dangerous loss of containment.

Explosion vent panels

This can be mitigated by an explosion vent panel, which is an intentional ‘weak spot’ in the wall or roof of the dust collector where an explosion can vent in a safe direction.

The explosion isolation backflap valve and the explosion vent panel must be carefully designed using the explosion characteristics of the combustible dust.

Combustible dust testing

All particles in motion can build up an electrostatic charge.

If the dust is insulating, the charge can accumulate on hot surface of the particles and transfer to the filter cake.

If this charge accumulates and then discharges to an earthed metal object, the spark can ignite the combustible dust.

The combustible dust explosion laboratory tests can test for the insulating tendencies of the dust and determine how much energy is required for the minimum ignition amount (Minimum Ignition Energy, MIE).

If the dust is insulating with a small minimum ignition energy, filters may need to be anti-static and have reliable contact with the earth.

Conclusion

Dust is a common hazard in many workplaces and industries, and it can pose serious risks to both workers’ health and safety and the environment.

That’s why it’s important to have suitable mechanisms in place to control hazardous dust and prevent combustible dust accidents.

In this article, we provided an overview of how to choose the right control measures based on the flammability of the dust.

We’ve also discussed the fire and explosion hazards of local exhaust ventilation (LEV) systems and how to avoid them.

It’s essential to follow the regulations that apply to your industry, such as COSHH and DSEAR, to ensure you’re taking the necessary precautions to protect your workers and your working environment.

You can find guidance documents on the HSE website or use a reputable process safety testing and consultancy house to help you determine what control measures are required for your specific situation.

It’s crucial to ensure that your local exhaust ventilation systems are properly maintained and operated to prevent the unintended consequences of dust accumulation, such as secondary explosions and fire.

By prioritising worker safety and taking the necessary precautions to control your combustible dusts, you can create a safer and more productive work environment for everyone.

References

[1] HSG 258: Controlling Airborne Contaminants at Work: A Guide to Local Exhaust Ventilation (LEV). §327-330.

[2] HSE: The technical basis for COSHH essentials: Easy steps to control chemicals.